Stock to demi-glace to glace de Viande.

Reducing and further refining your reductions to make glaze.

The good news is – the hardest part is behind you.

At this point the liquid, bones and vegetables are run through a china-cap for their initial strain and the stocks are moved into smaller pots. China-caps are great for the first strain because they’re deep and conical, allowing the stock to be poured rather aggressively into the next pot without much dilly-dally and they catch anything trying to spill out to the edges.

Shallow, bowl shaped strainers or small conical strainers are woefully inadequate for the job. They can lead to great heartache as you watch hours and sometimes days of your labor splash all over the place or head for the drain. I do my straining in the sink, for obvious reasons. China-caps do an adequate job at straining your initial batch and are the standard for getting us to the next stage. But what you make up for with convenience you pay for in quality, as they leave in many of the smaller solids. A fine mesh chinois is the ultimate tool for removing most of the solids, but should only be used on the second strain. They will immediately clog given the density of what’s to be filtered the first time around. Subsequent strains are great with the finer mesh and smaller chinois are helpful later on.

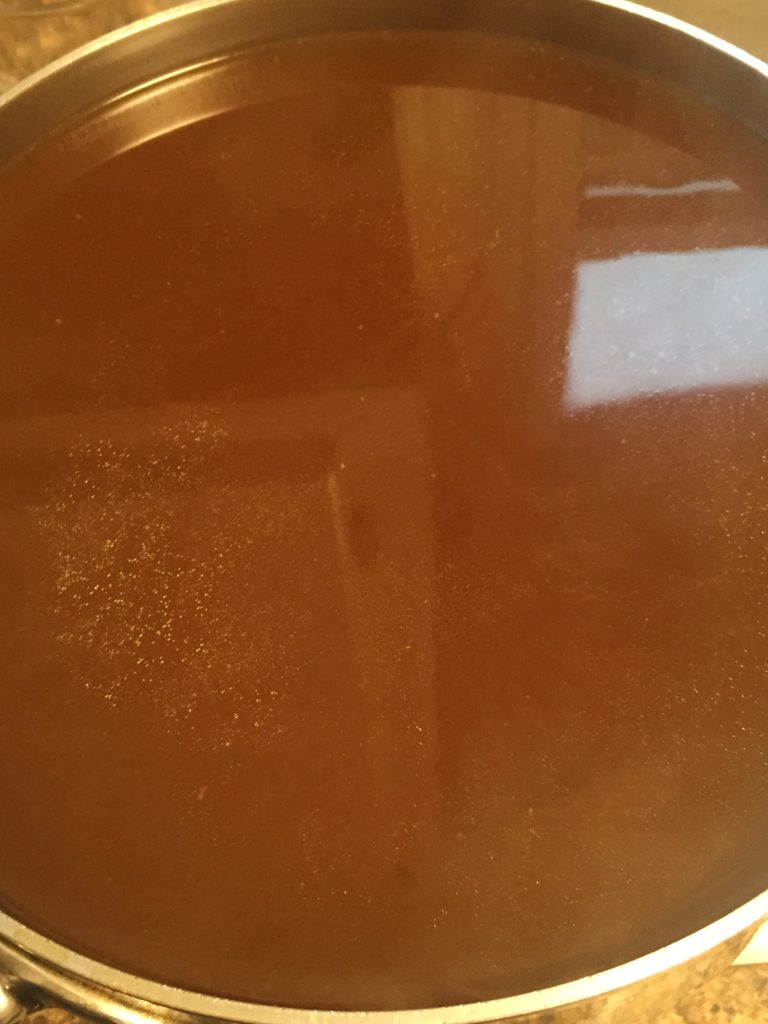

Once you’ve reached this stage, “all will be revealed” or almost all. The wonder and fantasy in great reductions kind of begins at this point. The ballet between the viscosity of the reduction and the intensity of the flavor begins. This is where all of your earlier decisions begin to reveal their irreversible impact on the flavor of your finished sauce. If you did things correctly up to this point you’ll be able to further adjust the viscosity of the final reduction without adversely effecting the flavor of the end product.

If you salted your mirepoix too heavily, over roasted your bones or added anything funny to the pot such as livers and the reduction has gotten even slightly off-tasting, you’re done, finished, finito. You’ve screwed the pooch. No poor tasting concoction at this stage is going to turn into a good glace. You’ll only intensify the bad flavor and try as you may, there’s no way to rescue it. You’re stuck with the thickness of the reduction as it is. It will never make a good glace and you shouldn’t reduce it any further.

However all is not lost provided it hasn’t gone completely over the edge. If your stock has intensified too much or demonstrates an off flavor which you can’t really identify, stop reducing, strain the sauce into a pyrex or NSF-approved plastic cambro style container, cool uncovered, then chill. Save the liquid for something where it can be diluted and live to fight another day. A nice roux will help it slide into a soup or stew that is pretty palatable. Try to go back in time and extrapolate what addition might have sent it down the crazy hole.

The real challenge and learned part of the process is to know how something is going to taste long before it is ever cooked. How a stock tastes at 1 hour is no indication of anything. How it tastes after 12-24 hours will tell you all you need to know. What you’re really in the business of doing is guessing how it’s going to taste many more hours down the road and that takes some experience, method and practice. Once again, it boils down to not doing the wrong things, which are much easier to tell you than exactly how to do it right.

The worst offenders will be bitterness from burning your bones or adding non-traditional vegetables or fruits. Don’t be tempted to throw various odds and ends into your stock-pot, like green bell peppers, or you’ll be sorry. I’ve seen entire pots of stock go down the sink because some less-than-helpful server thought to throw cut lemons into an unattended pot. I’ll never forget the sight of a sous chef running across the kitchen with a look on her face like I was getting ready to perform open heart surgery on a patient with bare hands after servicing a transmission, just to stop me from throwing a fist-full of scallion tops into a 100-gallon steam jacketed kettle bubbling away in the corner. The other items which can occasionally cause trouble when reducing stocks to glace, are the outer skins, leaf-ends or root ends of your mirepoix vegetables, but that’s something some chefs love to debate. For stocks I use everything but the ass-end of the celery. For glace I’m a little more discerning. The ultimate killer is the addition of salt in the reduction process.

The other “You should have known” is not to use an aluminum stock pot or saucier for the reduction. I can think of no greater sense of yuk than a glaze or reduction sauce brought down for hours in an aluminum pan or pot. Simply yuk. Don’t do it. You might get away with light broths and stocks in aluminum – but certainly not reductions.

Anyhoo…

When going from a 20qt pot to a 10qt pot, there’s usually a small amount that won’t fit into the pot on the next stage down. In this case I reserve the additional stock off to the side and add it a little at a time to the active reduction once there’s enough room. Eventually, everything which was in the big pot will now be in a pot approximately half the size of the first.

My process, to which I strictly adhere, is that each time my stock and subsequent sauces reduce by half, I move them to new, smaller pots, progressing through my saucier collection to whatever desired end-point. The heat is adjusted incrementally lower at each step. Every time the pots are changed, the stock is strained and skimmed, all the way down to glace if that’s where we’re headed, which in this case, we are.

For the veal stock in this run, the bones were strained off and everything in the pot was reserved. It was refilled with water, had more mirepoix added and was cooked again. also known as remouillage, or “rewetting”. So if you’re keeping score, that’s 40 quarts of stock, bone and vegetables which had an ultimate yield of 8 quarts of final reduction.

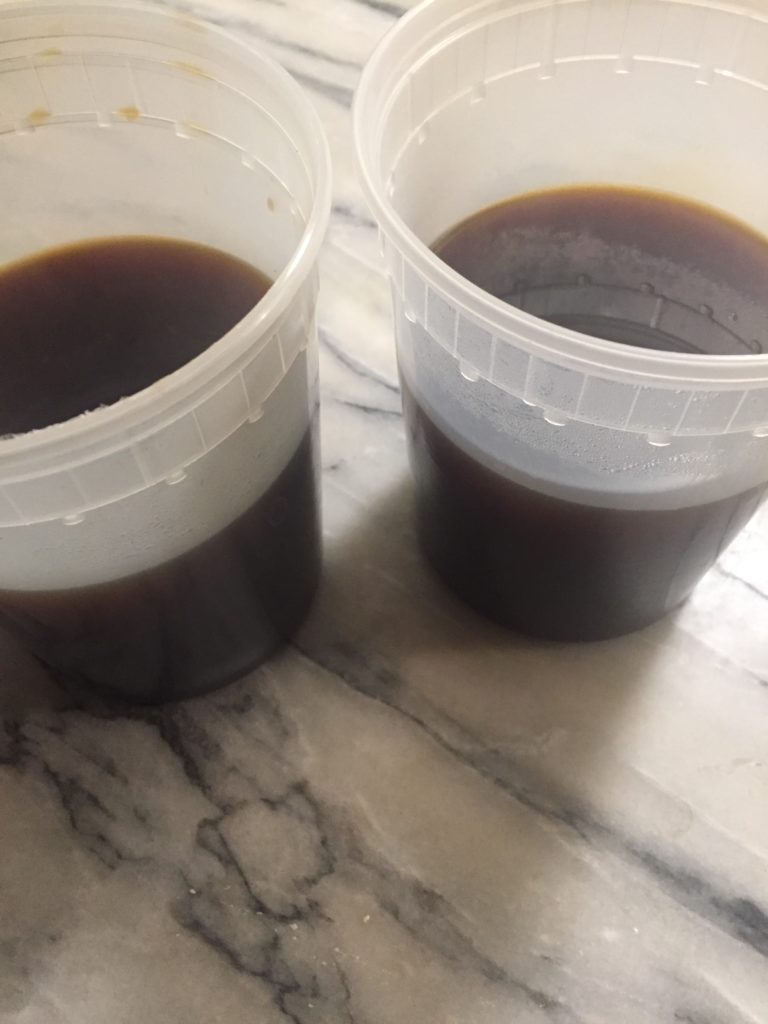

Approximately 4 quarts went through progressions to Sauce Espanole and eventually 2 quarts of Demi-Glace, in it’s truest form and was split between myself and a chef friend. The last few quarts were used for some braised lamb shanks and the rest… pretty much claimed by my wife and used in an assortment of dishes.

The following week the entire process was repeated. A few quarts were reserved as simple stock reductions, and the final 3 quarts were taken down by 2/3 to create our glace de viande, which you’ll see a little further down. In total, 35lbs of veal bones and some various beef trimmings were split between the two batches. I’m sure you can better understand the cost prohibitive nature of making these stocks, as well as the labor involved. Don’t go into it thinking it’s going to be a cakewalk.

On a side note about Demi; A lot of what you see online isn’t a true demi-glace, at least not according to the Le Guide Culinaire. People have made and placed online, nauseatingly long videos about the making of demi-glace and how to do it incorrectly. Some have written even more nauseatingly long articles… He writes with a smile…

The chicken, or poultry glace, went through its progressions from 20 quarts total volume into one quart final output. The color is a little deceiving in the pictures and the stock should have been photographed on a plate, but know that it ran a very dark crimson across the back of a spoon. This batch went on to flavor rice dishes and cooked lentils mostly. I don’t regularly go this deep on my poultry reductions, but for the purposes of this writing I wanted to take this stock there. Normally I fill my pot, slow burn it down by half and call it a batch. I get a lot more out of it that way, and we use it in everything.

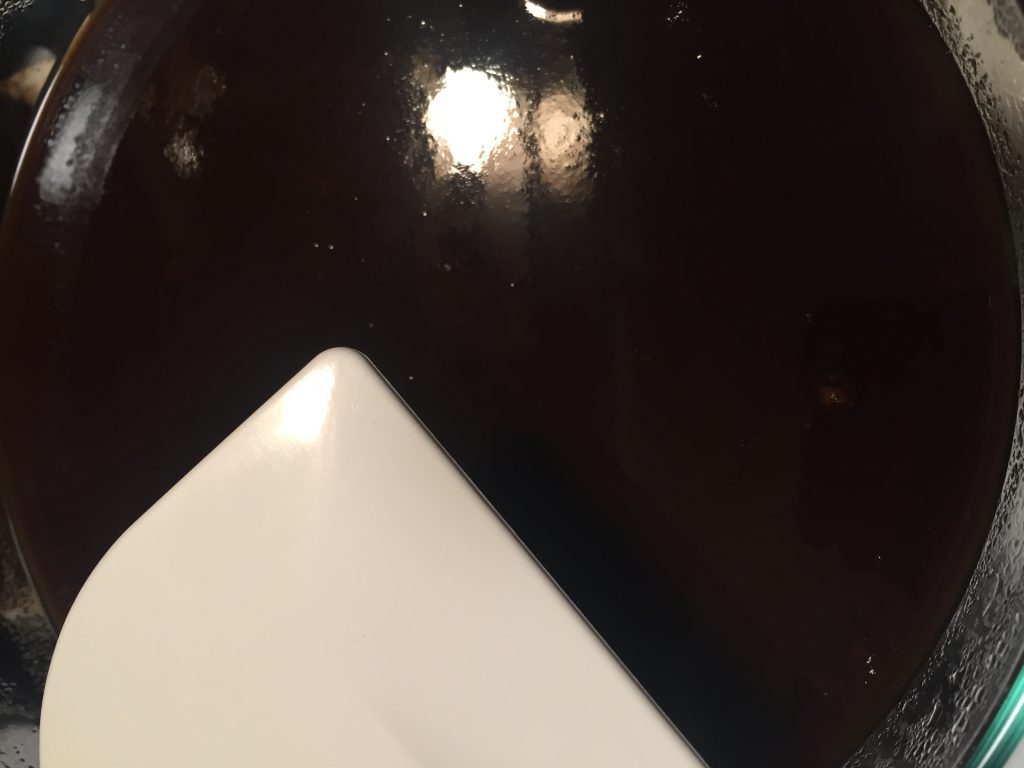

For our Glace de Viande, the final 3 quarts of an 8:1 reduction (40 quarts into 5) were very slowly brought down to one quart through what I can best describe as an “evaporative process”. The liquid is not really simmering, merely resting with enough heat under it to give it a slight shudder, or shimmer, with the occasional bubble breaking the surface. This is where the diffuser is kitchen gold, because it makes the constant temperature possible. At this density too much heat would burn it up, burn it away or both. The diffuser is priceless at this point. You can see the final 3 stages of the Glace de Viande in the following video.

In the video you’ll see the beginning reduction rate, the increase of activity in the reduction as it is finishing, and the solid composition of the chilled glace. Not a lot of wiggle in it when you smack it with a spoon. Almost none.

The chilled glace is sectioned into cubes, or in this case 1x1x2″ rectangles and placed in vacuum packed freezer bags for later use in finishing sauces for lamb, beef, game or just about anything which requires the flavors only a good glace can bring.

When it comes to beef, game or fowl stocks, the same rules apply as far as base vegetables and process, though you can add a lot more time for proper beef or veal stock. The rules change a lot when it comes to fish and truth be told, I’ve never made a fish glaze. When it comes to fish and shrimp stock I rarely go more than a few hours and sometimes far less. I like fish… A lot. But fish glaze is one thing I’ve left on the table for another day… someday when I get tired of the challenges posed by all the other proteins on earth.

So, to sum things up – finally.

If you have the time, patience and desire to work on deep, rich rewarding stocks – I recommend you get started learning the ins and outs and don’t be afraid of making mistakes. It’s how we learn. I remember the oopsies far longer and with more clarity than I do all the things which went well over the years.

If you desire rich sauces and meat glazes and don’t have the time or wouldn’t take the time, reductions of braising liquid are for you. The same process applies, but without the stock process. You’ll have wonderful pan reductions in a fraction of the time that it takes to make traditional glace and demi-glace. It’s ok. I won’t tell.

Just be patient no matter what you do. Take your time. Learn your method and study your results so that you can duplicate them without really trying. There’s a great world of mystery and excitement happening on stove-tops everywhere. Hopefully this has pulled the curtain back a little and temped you to walk in and start orchestrating the show yourself.

As with anything having to do with food, your mileage may vary. If you ever have any questions about undertaking any of this in your own kitchen, you’re always welcome to ask me questions in the comment section under this article. I’ll be happy to lend an ear and a hand to help you out. Don’t hesitate to ask. I just prefer you do it on the website so that others can learn from the Q&A as it happens.

– The Chef

Click here for Part 1 – Introduction to reduction stocks and glazes, or glace.

Click here for Part 2 – Some thoughts, roasting bones and preparing mirepoix.

Click here for Part 3 – Reducing, skimming and fortifying your stock.

Leave a Reply